History in the port area

Historians report that during the 18th century and part of the 19th century, approximately one million Africans disembarked in Rio de Janeiro, precisely at Valongo Quay. Directed to the fattening warehouses or cemeteries, these Africans populated the port area, tenements, and slums. Some names have been given to this region, from Little Africa to the current Porto Maravilha, despite the memories of suffering when people were traded as “things”, added to the pain of the present, in the face of repeated removals for reasons of real estate speculation.

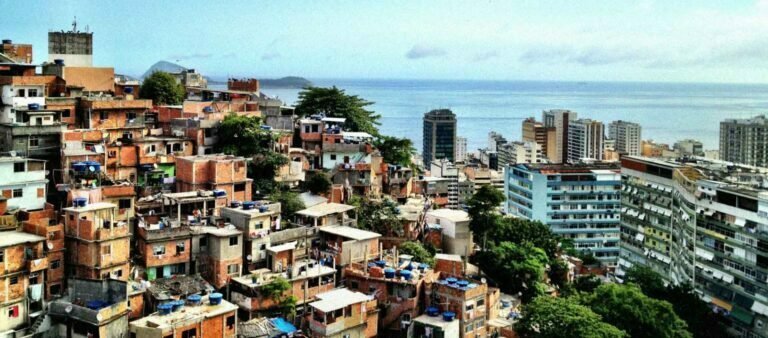

With the abolition of slavery in 1888, freed slaves, initially from Bahia in search of alternatives for survival, joined the Portuguese and poor Brazilians. It was these children and grandchildren of African slaves who brought samba, capoeira, and carnival to Rio de Janeiro, such as the famous João da baiana, grandson of former slaves who introduced the tambourine to samba and made a name for himself in the city’s rounds at the end of the 19th century. The search for opportunities, given the decadence of sugar with the end of slavery in the Northeast, consolidated the first favela in Rio de Janeiro, the Favela da Providência, an area that until then served mainly as a residence for former combatants of the Canudos War, also from Bahia.

With the first years of the Republic, at the beginning of the 20th century, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo hosted the country’s first textile factories, which used cotton from Maranhão as raw material, exporting and selling it to the domestic market. The Brazilians, former slaves and unskilled European immigrants were left with temporary jobs in the port while women and children joined the ranks of workers without social protection and low wages in the newly opened textile factories. Female and child labour was looked upon favourably by employers, as they made few claims for rights and wages. However, contrary to such thinking and the common sense of the time, women-led the first strikes in the textile mills of the early twentieth century in Rio and São Paulo, infecting female contingents in other cities such as Porto Alegre, in the south of the country.

The competitiveness of North American cotton and the struggle for rights made real estate speculation in the city a more profitable business than factory production. The result of the closure of the textile factories in Rio de Janeiro was the transformation of the huge working-class neighbourhoods built with loans from the Bank of Brazil at the beginning of the last century, into the present-day suburbs and some of the favelas of the metropolitan region.

Invisible value chains

However, slavery persists and sewing remains a means of survival for many women living in the port area. These women work mostly individually in their small rooms, where sewing machines and needles mingle with children and games or in old city tenements subcontracted by clothing manufacturers, with delayed wages, tight deadlines, exposed electrical wiring and degrading sanitary conditions. Integrated into invisible production chains, such as beachwear and carnival, they do not attract inspections about slave labour for reasons of safety, culture and stigma, despite the exhaustive work shifts and serious labour violations.

During summer and carnival, given the seasonality that characterises the two production chains, there is an exponential increase in orders, accompanied by an increase in labour supply, resulting in a drop in the remuneration paid per piece produced. Debts are their faithful companions, aggravating the vulnerability to exploitation, with impacts on the mental and physical health of the women as well as their children and grandchildren.

It is in this context that the project Sewing My Rights was developed, supported by the Brazil Human Rights Fund, with the objective of combating child slave labour and focusing on the city of Rio de Janeiro. Given that child labour is usually the result of the exploitation of mothers and women deprived of their freedom of choice to support their families, the project included mothers and grandmothers with their children and grandchildren. Considering that the experience of the people on the spot and the knowledge acquired from directly experiencing the problems are conditions for a successful search for solutions, a partnership was established with the sewing cooperative Cooperativa Maravilha, a cooperative of women living in the Favela da Providência.

Maravilha Cooperative

The Maravilha cooperative occupies an old shed located in the port area because of an agreement with Rio’s City Hall and survives by producing clothes for beachwear and gyms in the south and north zones of the city. The Cooperative’s main challenge is to break the cycle of exploitation by encouraging the formation of associations.

In its first stage, the Sewing My Rights project sought to identify, through focus groups, what the priorities of the 14 women living in Favela da Providência were. The need for a greater number of members and for an exchange of information on rights, access to justice, the functioning of the production chain and entrepreneurship were among the main demands from the women’s point of view. As a result, the project organised a sewing training course, led by a sewing teacher from the community, attracting a greater number of women interested not only in learning but in joining the Maravilha Cooperative. Furthermore, during the sewing course, during the 40-minute break, intense debates were held on the themes highlighted above, always arousing great interest and participation from all.

With the pandemic, the talks and discussions continued virtually, and themes related to the clothing sector, capitalist system in its current phase and flexibilization of labour rules entered the debates. Such conversations reached an even greater number of people in a virtual environment, reaching 34 assistants connected from their homes in the slum. Those with sewing machines and mobile phones can participate in the meetings. In this way, in an informal environment, before the pandemic, with coffee and cake offered by the women during the breaks, dreams were woven amidst personal revelations, resulting in transformations and learning, which remain amidst the virtual discussions during the pandemic.

In parallel, the children were motivated to dive into the same themes in a playful way, accompanied by a psychologist and recreationist, a woman resident of Cantagalo Favela, and manager of the local children’s library. Currently, the project with the children is being implemented in Cantagalo under the leadership of this woman resident, in the library building. A comic book was produced, Turminha da Providência, Resgatando a Cidadania, whose story was made with the collaboration of the children’s tutor staff, with the children of the project as the heroes of the story.

The testimonies of the mothers and grandmothers underline the value of enjoying a moment of learning, where they were unconcerned about their children and grandchildren, exchanging ideas, knowledge, and relevant information. Attention was drawn to children and young people with speech, motor coordination and mental disability who showed significant improvements, enjoying the exclusive time of constant cognitive stimulation.

The Continuity of the Project

The COVID-19 pandemic placed the group of seamstresses on the front line of the fight against the virus. With the financial reorganization of the project due to the pandemic, the group decided to invest resources in the purchase of raw material for the manufacture of 3,000 masks by the associates and students, in addition to food baskets that were donated to public health clinics in the region and families in the Favela da Providência.

The Sewing My Rights project and the support network it encouraged also contributed to the realisation of an old dream of the Maravilha Cooperative women’s group, the creation of a community day care centre in the Favela da Providência. Led by the director of the Maravilha Cooperative and making use of virtual funds, a campaign was started on social media, and the Anita Way day-care centre is rising up as a result of the struggle of the community’s residents and the support of a network of people, students, teachers, residents, who believe in education, citizenship and the power of association as instruments to combat social exclusion and submission to forms analogous to slavery in the 21st century.